For nearly a half century, Helen Redman has been making art. Her stunning portraits and evocative mixed media track events, both momentous and ordinary, in women’s lives. Much more than a visual, representational account of one woman’s perspective on life, her works illuminate something transcendent: they compose a visual memoir of the flux and flow of embodiment and identity across a woman’s life cycle, a memory-laden landscape of time’s passing in a life lived through a certain era and in a particular body.

In prose works of personal non-fiction, a writer creates movement, achieves a dynamic tension in her subject through a kind of self-investigation that establishes empathy by enabling readers to “see the ‘other’ as the other might see him or herself.”[i] No mean feat, its achievement depends on the creation of a narrator who can tell the self’s story in just the right tone, and at the distance needed to sustain the reader’s engagement, while also implicating the story-teller in the situation described, allowing us to observe “the mind puzzling its way out of its own shadows.” [ii] One can see the same process at work in Tensions in the Journey: From Child to Crone.

Like memoir, Redman’s portraits and self-portraits create something larger out of a singular life. Although drawn from the artist’s own experiences, often tracking changes in her own body, her visual self-investigations arc toward angles of insight and remembrance wider and deeper than one woman’s life. Turning her steady gaze toward scenes from her own life, Redman captures in bold, even garish, yet always emotionally resonant strokes, the varied, sometimes conflicted, experiences of womanhood’s vicissitudes. Her portraits offer a visual representation of a “mind puzzling its way out of its own shadows.” And because we see the thinking mind at work, these representations push beyond the boundaries of the figurative aesthetic they share, gesturing toward the conceptual art of a later period.

In the mid-1970s, Adrienne Rich was among the first feminist writers to articulate how, at the heart of birth-giving, anxiety twins with awe:

Nothing could have prepared me for the realization that I was a mother....Nothing... prepared me for the intensity of relationship already existing between me and a creature I had carried in my body and now held in my arms and fed from my breasts...No one mentions the psychic crisis of bearing a first child....No one mentions the strangeness of attraction...to a being so tiny, so dependent, so folded-in to itself—who is, and yet is not, part of oneself. [iii]

A decade before Rich’s commentary, Helen Redman began plumbing the depths of our being “of woman born.” An album of visual discoveries, a memory bank of images, her portraits are reflections on the complexities—the tension and delight—at the heart of female embodiment and sensuality.

In Nicole on My Knees--the artist’s early portrait of her daughter --we see the child seated on her mother’s lap, her head cradled in the right angle made by her mother’s knee while the mother’s right ankle rests across the thigh of her left leg. The child’s gaze fixed on the mother, the mother’s torso framing the child, we see the child, literally, from the mother’s perspective. But since the artist’s point of view is simultaneously the mother’s point of view, which becomes the viewer’s point of view, the portrait achieves a visual triangulation that defies the culturally presumed contradiction between the activities of mothering and art-making.

In Nicole on My Knees--the artist’s early portrait of her daughter --we see the child seated on her mother’s lap, her head cradled in the right angle made by her mother’s knee while the mother’s right ankle rests across the thigh of her left leg. The child’s gaze fixed on the mother, the mother’s torso framing the child, we see the child, literally, from the mother’s perspective. But since the artist’s point of view is simultaneously the mother’s point of view, which becomes the viewer’s point of view, the portrait achieves a visual triangulation that defies the culturally presumed contradiction between the activities of mothering and art-making.

Unlike the traditional voyeuristically rendered and romanticized “Madonna and child,” this portrait announces the possibility of nurturing life while sustaining one’s art. Yet, notice something further. Below the bench where the mother/artist is seated the pattern and color of the carpeting mimic, in angle and tone, the positioning of the viewer in the place of the mother/artist, suggesting that both mothering and art-making require “worldly” support, or repetition, to ground, sustain, and renew them. Receiving the child’s gaze through the mother/artist’s eyes enables the viewer to question both the traditional assumption that motherhood negates women’s subjectivity, and the early second wave feminist assessment of motherhood as the root of women’s oppression.

Still, the anxiety Rich describes about mothering lingers thematically and aesthetically in Redman’s image. Having “cut off” the rest of the woman from the part of her body on which the child rests, the portrait risks evoking an uncanny “corps morcelé”[iv]—an adumbration or mutilation of the mother’s body. Has the child’s wholeness been achieved at the expense of the woman’s? Yet, the artist’s imaginative rendering of herself both inside and outside the frame renders the lived body of woman/mother/artist whole again. The artist brings the almost-forgotten living body/mind of the image’s creator to our consciousness, enabling the woman/mother/artist to re-emerge in our mind’s eye, shimmering with multidimensional life.

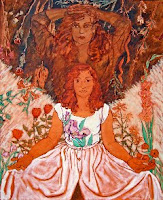

If Nicole on My Knees explores the anxiety around the woman artist’s disappearance into the role of the mother, Nicole and Her Shadow focuses tensions surrounding the daughter’s “second birth” into adult womanhood. Echoes of the myth of Demeter and Persephone abound in this rich, allegorical oil painting of what, at first glance, seems a testament to a young woman’s sensual, sexual awakening.

Nicole’s posture and demeanor suggest the naïf her mother (and who else?) imagines—or  wishes?—her still to be. Notice, though, how the young girl’s skirt parts open, willfully or not, revealing a dark triangle, the entrance to sexual pleasure, already aroused. As the viewer’s eye is drawn to this space it is as if the more mature, seductive Nicole—Nicole’s “ shadow” —has only been waiting to be seen; she begins to loom larger, becoming more potent.

wishes?—her still to be. Notice, though, how the young girl’s skirt parts open, willfully or not, revealing a dark triangle, the entrance to sexual pleasure, already aroused. As the viewer’s eye is drawn to this space it is as if the more mature, seductive Nicole—Nicole’s “ shadow” —has only been waiting to be seen; she begins to loom larger, becoming more potent.

The field where the younger Nicole sits now curves toward this darkened upper portion of the painting, framing the Nicole of the shadows as if in the oval of a mirror. In contrast to the younger Nicole’s seemingly demure posture, this “other” Nicole, arms raised behind her head, framing her voluptuous face, beckons us closer with an eroticism unsettlingly frank and self-possessed, taking as much pleasure in her own image as in its imagined effects on the viewer.

And just as Demeter’s grief at Persephone’s annual return to the underworld leads Demeter to render the fields fallow, so does this doppelgänger Nicole-in-the-underworld stand against a darkening background littered with shriveling red flowers. Is this painting, then, a warning, or a plea to return to innocence? The eye travels between these two Nicoles, the girl birthing the woman, the woman rebirthing the girl, and suddenly the painting’s gesturing toward the cycle of departure and return takes on a deeper meaning.

“To ‘feel into’ the season of winter; to take into one’s self the barrenness, the dormancy, the separation from and seeming cessation of life; to experience it all as if it were the loss of the Kore child [Persephone]...raging over all of the places where life spirals downward... is the start of initiation,” wrote the psychologist Kathie Carlson about this ancient Greek myth. “But to follow Persephone on this path, to see her in Nature, is also to experience return...She returns and, with her, the dead are reborn, blossoming forth like flowers and grain...only to begin....the whole cycle again.”[v]

Neither warning, nor plea, the painting reminds the viewer how we are each implicated in life’s cycle of loss or separation: no transformation without shadows following behind, and those ahead beckoning us on.

Feeling into the winter season of her own life’s odyssey, Redman’s stark images in The War at Home, offer a comic, yet sobering, look at menopause, a time of brittle bones and bitter herbs, when a woman becomes more aware of death’s knocking on the door of her consciousness.

Feeling into the winter season of her own life’s odyssey, Redman’s stark images in The War at Home, offer a comic, yet sobering, look at menopause, a time of brittle bones and bitter herbs, when a woman becomes more aware of death’s knocking on the door of her consciousness.

Redman stages this war in the home of her body and at the wisdom sight, what yogis call “the third eye,” pathway to the true self. On one side the aging physical body sits comfortably, in half-lotus pose. Is this body in a state of delusion, ignoring its inevitable demise? No matter. Death, that ghoulish boxer, delivers a quick right jab to the head: Eyes and ears open! Arise from your slumber! Don’t give up! Like Krishna’s advice to the warrior Arjuna in The Bhagavad Gita, the visualized response of that rakish boxer in Redman’s portrait startles the complacent skeleton back to life: “From the world of the senses comes...pleasure and pain. They come and they go. Arise above them, strong soul.”

And just below this battle, positioned at the throat chakra, or the region of one’s inner, truthful voice, a prostrate figure of the artist lies in the solemn yoga pose, kurmasana, or turtle pose. Hunched over, she honors the last long flow of blood emanating from her body, accepting that body’s own future in the outstretched skeletal arms formed by the exposed clavicle above the heart, before she begins the long journey home to what remains.

In one of her most recent compositions, On Our Path, two pairs of feet, standing in an interlocked pose, symbolize the intergenerational  nature of Redman’s continued journey, as an artist and as a woman. “The golden young feet moving forward are those of my granddaughter Shira. The old wood textured feet astride and behind her are mine. The setting is shoreline and our interlocking stance is a caress...The vision...came to me one morning while doing Qi Gong.”

nature of Redman’s continued journey, as an artist and as a woman. “The golden young feet moving forward are those of my granddaughter Shira. The old wood textured feet astride and behind her are mine. The setting is shoreline and our interlocking stance is a caress...The vision...came to me one morning while doing Qi Gong.”

Redman’s interpretation of her own work provides important perspective on her aesthetic and thematic choices. As in her other mixed media pieces, textures matter as much to the painting’s narrative as color and line. “The river of life, a stylized water pattern of intense blue and white, is unpredictable, both caring and cutting in its randomness,” the artist continues. Below the surfaces, in between the images, lies the invisible traces of the deepest truth Helen Redman’s art has plumbed: we are the women we have made ourselves become with the circumstances of a life none of us chooses to start on our own.

(Watch a video interview with artist Helen Redman here.)

[i] Vivian Gornick, The Situation and the Story, 35.

[ii] Ibid., 36.

[iii] Of Woman Born, 17.

[iv] According to Jonathan Kim-Reuter, “Corps morcelé” is a term associated with the Jacques Lacan’s psychoanalytic theory and “refers to what he understood as the earliest sense of the body registered by the human being in the infant condition, when, prior to the stabilizing effects of what is known as “the mirror experience” [seeing the reflection of one’s image as a coherent whole], the body image is mostly a chaos of affective and sensory phenomena.”(personal correspondence). The sense of being a part and not a whole can recur, in adulthood, through trauma. Rich describes the woman’s sense of being “out of body” in birth and mothering in terms echoing the anxiety surrounding corps morcelé. Nicole on My Knees acknowledges this anxiety, yet transcends it.

[v] Life’s Daughter/Death’s Bride, Shambala, 1997.